Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

Loading...

CalHHS programs are required to provide public reporting based on federal and California statute and regulations, court orders, and stipulated judgments, as well as by various funders. Although reporting may be mandated, unless the law expressly requires reporting of personal characteristics, publicly reported data must still be de-identified to protect against the release of identifying or personal information which may violate federal or state law.

Survey data, often collected for research purposes, are collected differently than administrative data and these differences should be considered in decisions about security, confidentiality and data release.

Administrative data sources (non-survey data) such as: vital statistics (e.g. births and deaths), healthcare administrative data (e.g. Medi-Cal utilization; hospital discharges), reportable disease surveillance data (e.g. measles cases) contain data for all persons in the population with the specific characteristic or other data elements of interest. Most of the discussions in this document pertain to these types of data.

On the other hand, surveys (e.g. the California Health Interview Study) are designed to take a sample of the population, and collect data on characteristics of persons in the sample, with the intent of generalizing to gain knowledge suggestive of the whole population.

The sampling methodology developed for any given survey is generally developed to maximize the sample size with the available resources while making the sample as un- biased (representative) as possible. These sampling procedures that are a fundamental part of surveys generally change the key considerations for protection of security and confidentiality. In particular, the main “population denominator” for strict confidentially considerations remains the whole target population, not the sampled population. But, if persons have special or external knowledge of the sampled populations (e.g. that a family member participated in the survey), further considerations may be required. Also, it is in the context of surveys that issues of statistical reliability often arise—which are distinct from confidentially issues, but often arise in related discussions.

Of particular note, small numbers (e.g. less than 11) of individuals reported in surveys do not generally lead to the same security/confidentiality concern as in population-wide data, and as such should be treated differently than is described within the Publication Scoring Criteria and elsewhere. In this case a level of de-identification occurs based on the sampling methodology itself.

The CalHHS Data Knowledge Base is composed of three main parts. These have historically been siloed documents, however, have now been published together to serve as a point of truth guide for all CalHHS data sharing needs.

As a product, the Knowledge Base is maintained by the Center for Data Insights and Innovation. It will be reviewed at least annually to ensure base functionality, such as no broken links, etc. For questions or contribution suggestions, please email [email protected]. Each section or component of the knowledge base will have it's own governance, update cycle, and contact information. Please see below.

The Data Sharing Guide was created in 2024 by the CalHHS Office of Technical Systems Integration (OTSI). The content of the previously published CalHHS Data Playbook and Data Playbook-Beta has been merged with this new sharing guide. If you have questions or ideas to contribute to the Data Sharing Guidebook section, please email .

The Numerator – Denominator Condition represents a combination of both the Numerator Condition and Denominator Condition and for which both conditions must be met or else a more detailed assessment is required. This may be considered as an initial screening of a data set.

The Numerator Condition sets a lower limit for the cell size of cells displayed in a table. The DDG has set this limit as any value representing aggregated or summarized records which are derived from less than 11 individuals (clients). Of note, values of zero (0) are typically shown since a non-event cannot be identified.

The Denominator Condition sets a minimum value for the denominator. The DDG has identified the lower limit for the denominator to be a minimum value of 20,000.

Since this is a Numerator – Denominator Condition, both the minimum cell size for the numerator and denominator must be met. If these conditions are met, the table can move to Step 5 for consideration for release to the public. If either the numerator of denominator condition is not met, then the review of the data must proceed to Step 3.

Necessity of criteria for this step will be determined by each department. This may vary depending on the purpose of the release and whether or not the department or program is a HIPAA covered entity or not. See for further discussion.

This step requires the use of a documented method to assess the risk that small numerators or small denominators may result in conditions that put individuals at risk of being re-identified.

Assessment of potential risk for a given data set must take into account a range of contributing considerations. This includes understanding particular characteristics of a given data set that is being released. For example, if the potential values for a specific personal characteristic, such as race, results in many small numbers in data set A but does not in data set B, then the risk may be low for data set B and high for data A if the groupings of the personal characteristics include the same categories. For this reason, each department or program may set different values for risk based on the underlying distribution of these variables in the data sets of interest.

There are many methods used to assess potential risk. Many of the methods that are in use throughout the country are described in the various references provided in Section 15. While each department will document the method(s) chosen for use, the following description of the Publication Scoring Criteria is provided as an example and may be adopted by departments as a method to assess potential risk.

CalHHS implemented an agency-wide governance structure in October, 2014. The governance structure acts both in a decision-making and advisory capacity to Agency leadership and its departments and offices. Implementation of the governance framework supports information technology (IT) initiatives that are more tightly aligned with meeting business objectives, enhanced project prioritization and improved strategic IT investment decisions. The Executive Sponsor is the Undersecretary of CalHHS. The Advisory Council consists of representatives of senior leadership from departments and offices in the Agency. There are five subcommittees that report to the Advisory Council, which include the Portfolio, Procurement, Infrastructure, Risk Management and Data Subcommittees. The Data De-identification Workgroup was convened by the Data Subcommittee with representation from all departments and offices in CalHHS.

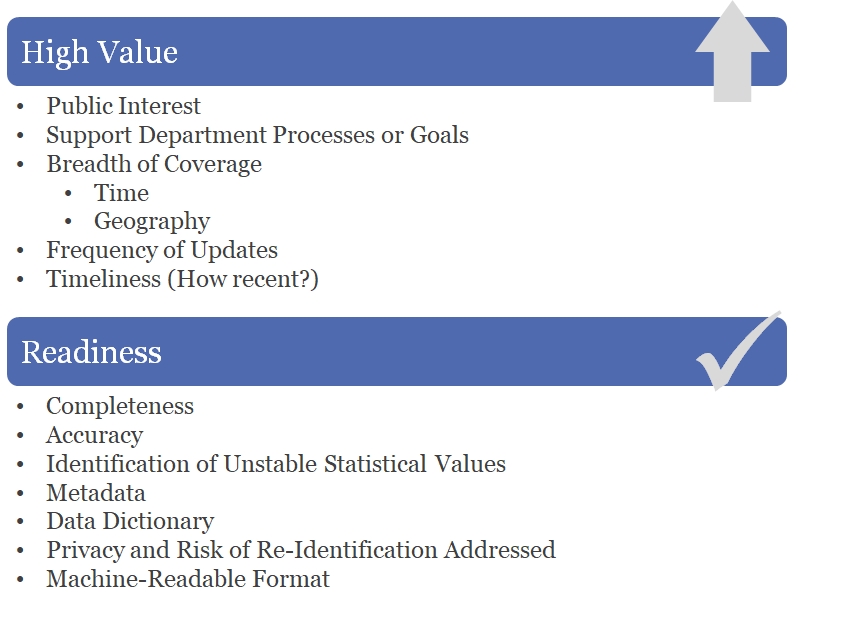

CalHHS is engaged in improving transparency and public reporting through the Open Data Portal. As described in the CalHHS Open Data Portal Handbook, not all data is suitable for use on the open data portal. Data is Publishable State Data if it meets one of the following criteria:

Data that are public by law such as via the or

As described in and Figure 2, personal characteristics of individuals introduce the most significant risk with respect to identifying individuals in a data set. The following are examples of personal characteristics.

Identifiers as defined in CA IPA

Identifiers as defined in HIPAA

Demographics typically reported in census and other reporting

The CalOHII is authorized by state statute to coordinate and monitor HIPAA compliance by all California State entities within the executive branch of government covered or impacted by HIPAA. To help ensure full compliance with HIPAA, CalOHII conducted a reassessment with all State Departments in January 2014 and updated as of July 27, 2015. The following are the self-reported results of this reassessment:

The Publication Scoring Criteria is used to identify the presence of small values that are considered sensitive in order to facilitate the assessment of potential risk. The Publication Scoring Criteria combines a number of conditions that increase the risk of a given data table and allows the department to evaluate those risks in combination with each other. The variables included in the Publication Scoring Criteria are those variables routinely used to publish data but are not all inclusive.

A variable is a symbol representing an unknown numerical or categorical value in an equation or table. A given variable may have different ranges assigned to it. Ranges assigned to the variable may be defined many ways which may increase or decrease the risk of identification of an individual represented in the table. This is seen in the Publication Scoring Criteria in that ranges for variables which will produce smaller groupings have a higher score.

The Publication Scoring Criteria in Figure 6 quantifies with a score two identification risks: size of potential population and variable specificity. The Publication Scoring Criteria is used to assess the need to perform statistical masking as a result of a small numerator, small denominator, or both. The Publication Scoring Criteria takes into account both variables associated with numerators, such as Events, and with denominators, such as Geography.

This method requires a score less than or equal to 12 for the data table to be released without additional masking of the data. Any score over 12 will require the use of statistical masking methods described in Section 4.4 or documentation regarding the specific characteristics of the data set that mitigate the risk.

When identifying the score for each variable, use the highest scoring criteria. For example if a table had age groups of 0 to 11 years, 12 to 14 years, and 15 to 18 years then the score for the “age range” variable would be +5 because the smallest age range is 12 to 14, which is an age range of three years.

If a variable has greater granularity than the score listed, use the highest score listed. For example, if the variable “Time” has a frequency of “weekly” then the score would be +5 which is the maximum score associated with the most granular level (monthly) of the variable in the Publication Scoring Criteria.

In addition to assessing the granularity of each variable, the interaction of the variables is also important. As discussed later in section 6.4, decreasing the granularity or the number of variables are both techniques for increasing the values for the numerators. The final criteria in Figure 6 is that for Variable Interactions. This provides for a subtraction of points if the only variables presented are the events (numerator), time and geography and an addition of points for including more variables in a given presentation. With respect to the subtraction of points, the score is based on the minimum value for the Events variable. For example, if the smallest value for the Events is 5 or more, then the score would be -5. However, if the smallest value for the Events is 2, then the score would be 0. This is discussed in more detail in Section 6.2: Assessing Potential Risk - Publication Scoring Criteria.

In assessing risk, the scoring can be part of the justification to release or not release data but should not by itself be an absolute gateway to the release data. The review must take into account additional considerations including those that are discussed in this document in addition to the scoring.

Data shall not be released if it is restricted due to the HIPAA, state or federal law. Data tables may fall into one of three categories:

Level One: Data tables that can be released to the public and published without restriction;

Level Two: Data tables that have some level of restriction or sensitivity but currently can be made available to interested parties with a signed data use agreement; or

Level Three: Level three data are restricted due to HIPAA, state or federal law. These data will NOT be accessible through the CalHHS Open Data Portal.

Data can change from being Level 3 to Level 1 if appropriate de-identification processes are employed. The CalHHS DDG described in this document will support departments and offices in the evaluation of data to determine whether it has been adequately de-identified so that it can be considered Level 1.

Race

Ethnicity

Language Spoken

Sex

Age

Socio-economic status as percent of poverty

Personal characteristics are those characteristics that are distinctive to a person and may be used to describe that person. Personal characteristics include a broader set of information than those data elements that may be specifically defined as identifiers (such as, driver license, address, birth date, etc.). Personal characteristics may also be inferred from characteristics related to provider or utilization data. For example, if presented with information about a provider that only sees women, it can be inferred that the clients are women even if that is not specifically stated in the data presentation.

The Data De-Identification Guide published here is the current approved CalHHS Agency De-Identification Guidelines. Each Department or Office within CalHHS can also publish their own version of the DDG. The refresh cycle of the Agency DDG is determined by the CalHHS DDG Peer Review Team (PRT.) As of January 2025, the PRT is currently developing an update to the Agency DDG with publication date TBD.

If you have questions about the governance around the Agency Data De-Identification Guidelines please visit the DDG Governance page.

If you need Department specific Data De-Identification Guidelines, or other Department specific data information, please contact that Department directly. This page on the CHHS website has links to each of the CalHHS Department and Office webpages.

The Open Data handbook is a resource with its audience being the CalHHS ODP+GIS Workgroup and those that publish or utilize the CalHHS Open Data Portal. As of February 2025, revisions are being made to the ODP handbook. Please see the ODP Governance page for more information. If you have questions or ideas to contribute to the Open Data section, email [email protected].

Many CalHHS programs oversee, license, accredit or certify various businesses, providers, facilities and service locations. As such, the programs report on various metrics, including characteristics of the entity and the services provided by the entity.

Characteristics of the entity are typically public information, such as location, type of service provided, type of license and the license status.

Services provided by the entity will typically need to be assessed to see if the reporting includes personal characteristics about the individuals receiving the services. Several examples are shown below.

Reporting number of cases of mental illness treated by each facility – if the facility is a general acute care facility then the reporting of the number of cases does not tell you about the individuals receiving the services.

Reporting number of cases of mental illness treated by each facility – if the facility is a children’s hospital then the reporting of the number of cases does tell you about the individuals receiving the services.

Reporting number of psychotropic medications prescribed by a general psychiatrist does not tell you about the patients receiving the medications.

Reporting number of psychotropic medications prescribed by a general psychiatrist to include the number of medications prescribed by the age group, sex or race/ethnicity of the patients receiving the medications does tell you about the patients receiving the medications.

In (a) and (c) above, assessment for de-identification is not necessary as there are no characteristics about the individuals receiving the services. However, in (b) and (d) above, the inclusion of personal characteristics which may be quasi-identifiers, especially when combined with the geographical information about the provider, does require an assessment for de-identification.

Taking the time to plan your project is essential. Whether you’re managing a team, analyzing or cleaning a portion of data, or drawing conclusions from your findings, completing any portion of the project requires a great deal of thought and planning. In the following section, we’ll provide a clear, step-by-step guide to the entire planning process, including everything you need to know about creating goals, determining a plan, and getting your data. It is our hope that you leave this section with a detailed and specific plan, and the confidence that you have the tools to carry out a successful project.

Be sure that you are measuring success and thinking critically about what your success metrics will be. You must have clear and actionable goals that you want to achieve with your data project.

Everyone is going to define data differently. Start by understanding what data means for your Department. It also will be important for you to prioritize your data. You must know which data are the highest value to your organization.

You’re going to want to be sure to start small. Running a few pilots around data can’t hurt; this will help you get a better understanding of the lay of the land, what you can improve with data, and how you can identify the gaps.

Every employee will need different kinds of accessibility, so make sure that your data systems maps to these needs and is not providing unauthorized access to information.

This will help staff clearly see the impact of the project and how data can improve effectiveness and efficiency. Including the Playbook in a new employee orientation could further enable staff and foster a culture of data within a Department.

Don’t have access to the IT services you need? Maybe there is a shared service you can use with other Departments, or there are easier ways to get access to contemporary technologies. It’s also possible that you could iteratively re-engineer your existing IT infrastructure to gradually meet emerging needs.

After completion of the statistical de-identification process, each department will specify the additional review steps necessary for public release of various data products. Products may include but are not limited to reports, presentation, tables, PRA responses, media responses and legislative responses. See Section 7: Approval Process for further discussion.

CalOHII......... California Office of Health Information Integrity

CDC.............. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CDPH........... California Department of Public Health

CDSS............ Department of Social Services

CHHS........... California Health and Human Services Agency

CMS.............. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

CPHS............ Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects

DDG.............. Data De-Identification Guidelines

DHCS........... Department of Health Care Services

HIPAA........... Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

IPA................. Information Practices Act

MHSOAC..... Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission

OSHPD......... Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development

PAR-DBR..... Public Aggregate Reporting - DHCS Business Reports

PHI................ Protected Health Information

PI................... Personal Information

PRA............... Public Records Act

PRT............... Peer Review Team

Governance for DDG will be provided by the Data Subcommittee with support from the Risk Management Subcommittee. The Subcommittees are part of the CHHS governance structure as described in the CalHHS Information Strategic Plan. Governance for the CalHHS DDG will provide the following support for departments and offices.

Maintain the CalHHS DDG, which will include updates and revisions to the document as well as annual reviews for currency.

Coordinate integration of the CalHHS DDG into the Statewide Health Information Policy Manual (SHIPM), Section 2.5.0 De-identification and the CalHHS Open Data Handbook.

Convene a Peer Review Team (PRT).

Provide for escalation of issues that cannot be resolved by the PRT.

The CalHHS PRT will include no more than two representatives from each department or office. Membership of the PRT is expected to include individuals with the following background and experience.

Knowledge of and experience with generally accepted statistical and scientific principles and methods for rendering information not individually identifiable.

Knowledge of and experience with legal principles associated with data de-identification in compliance with California IPA and HIPAA.

The PRT will have the following responsibilities:

Provide review and consultation regarding a department’s DDG to ensure it is consistent with the CalHHS DDG. This may be particularly useful if a department incorporates methods for de-identification in the department’s DDG that have not already been documented in the CalHHS DDG.

Provide for escalation and review of data de-identification questions or issues that a department is not comfortable resolving independently.

Develop training tools to be used by departments when developing and implementing department specific DDGs based on the content of the CalHHS DDG.

The PRT will not review all disclosures or data released by each department.

Aggregate – formed or calculated by the combination of many separate units or items (Oxford Dictionary).

De-identified – generally defined under the HIPAA Privacy Rule (45 CFR section 164.514) as information (1) that does not identify the individual and (2) for which there is no reasonable basis to believe the individual can be identified from it.

Denominator – the portion of the overall population being referenced in a table or a figure representing the total population in terms of which statistical values are expressed (Oxford Dictionary).

Numerator – the number of specific cases as identified by the variable from a given population or the number above the line in a common fraction showing how many of the parts indicated by the denominator are taken (Oxford Dictionary).

Protected Health Information – information which relates to the individual’s past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition, the provision of health care to the individual, or the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to the individual, and that identifies the individual, or for which there is a reasonable basis to believe can be used to identify the individual (HIPAA, 45 CFR section 160.103).

Personal Information – includes information that is maintained by an agency which identifies or describes an individual, including his or her name, social security number, physical description, home address, home telephone number, education, financial matters, email address and medical or employment history. It includes statements made by, or attributed to, the individual (California Civil Code section 1798.3).

Publishable State Data – Data is Publishable State Data if it meets one of the following criteria: (1) data that are public by law such as via the PRA or (2) the data are not prohibited from being released by any laws, regulations, policies, rules, rights, court order, or any other restriction. Data shall not be released if it is highly restricted due to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), state or federal law (such data are defined as Level 3 later in this handbook.)

Re-Identified – matching de-identified, or anonymized, personal information back to the individual.

The following list of variables is important to consider when preparing data for release.

Age

Sex

Race

Ethnicity

Language Spoken

Location of Residence

Education Status

Financial Status

Number of events

Location of event

Time period of event

Provider of event

As stated previously, variables that are personal characteristics may be used to determine a person’s identity or attributes. When these characteristics are used to confirm the identity of an individual in a publicly released data set, then a disclosure of an individual’s information has occurred. Individual uniqueness in the released data and in the population is a quality that helps distinguish one person from another and is directly related to re-identification of individuals in aggregate data. Disclosure risk is a concern when released data reveal characteristics that are unique in both the released data and in the underlying population. The risk of re-identifying an individual or group of individuals increases when unique or rare characteristics are “highly visible”, or otherwise available without any special or privileged knowledge. Unique or rare personal characteristics (e.g., height above 7 feet) or information that isolate individuals to small demographic subgroups (e.g., American Indian Tribal membership) increase the likelihood that someone can correctly attribute information in the released data to an individual or group of individuals.

Variables that are event characteristics are often associated with publicly available information.

Therefore, increased risk occurs when personal characteristics are combined with enough granularity with event characteristics. One could argue that if no more than two personal characteristics are combined with event characteristics then the risk will be low independent of the granularity of the variables. This hypothesis will need to be tested using various population frequencies to quantify the uniqueness of the combination of variables both the in the potential data to be released as well as in the underlying population.

Revision history for CalHHS Agency Data Sharing Guidelines

The Data Sharing Guidelines published here is a combination of the previously published CHHS Data Playbook, Data Playbook Beta, and the newly produced Data Sharing Guidelines from OTSI/CDII. The current version of the Data Sharing Guidebook is 1.0.

Data is a core facilitator for the California Health and Human Services (CalHHS) vision of:

“… a connected network of state, local, and community providers, an ecosystem of coordinated services, and the secure, appropriate use of comprehensive demographic, socioeconomic, encounter, and outcomes data to generate insights that drive equitable policies, programs, and service delivery.” – CalHHS IT & Data Strategic Plan, March 2024

With over 33,000 employees, we at CHHS make up the largest agency under California’s executive branch. Our 13 departments collectively have access to an unprecedented amount of data -- it is our mission to use this data to improve the programs and services we deliver to our clients, amplify the impact of the data reports we create, and to create an organizational culture that is focused on data-driven decision making.

Realizing this vision requires data flow across the Agency’s departments and partner organizations. The CalHHS Data-Sharing Guidebook’s purpose is to be an asset that is broadly applicable to departments with various levels of data-sharing capabilities and experience. The diagram below provides the CalHHS Data-Sharing Guidebook’s purpose in California’s data- sharing ecosystem.

The Guide is composed of two sections:

The Business Use Case Proposal Lessons Learned summarizes the learnings from data-sharing experts who participated in the discovery sessions used to create this Guide.

The Data-Sharing Plays provide how-to guidance to implement capabilities that help establish data-sharing agreements and deliver meaningful data.

The Guide is a supplement to existing data-sharing assets, including:

State of California

The CalHHS

Department-level data-sharing assets

The Guidebook is shared with you and your Department so you can use its content to supplement existing department data-sharing processes and training materials.

The Guidebook’s primary audience is data coordinators and data management teams that create data-sharing agreements, fulfill data requests, and consume shared data. The Guidebook’s Data-Sharing Plays also benefit your department’s data analyst, application development and security teams.

If not already in place, we recommend creating a centralized department-level repository of BUCPs and mechanisms to track data-sharing metrics. Your previous BUCPs are valuable assets. Create a centralized department-level document repository for your BUCP artifacts to:

Establish a library of reusable BUCP content to reduce content creation time.

Maintain templates such as standard security controls and forms required by your department.

Store reference material such as resolutions to disputes and solutions to statutory restrictions for data-sharing.

Store quantitative and qualitative information on data-sharing outcomes to include in business cases to invest in data-sharing.

A departmental-level view of all BUCPs also helps prioritize the data-sharing improvement efforts by identifying frequently requested datasets.

Your BUCP document repository can also be a resource for lessons learned as BUCPs are approved and fulfilled. Collect team input to create “lessons learned” that you gleaned from working through the BUCP process. Retrospectives are an effective way to engage your team to collect and document lessons learned. Feel free to use the CalHHS Data-Sharing Guide: Lessons Learned section as a starting point for your department’s lessons learned.

Make sure your data-sharing team is aware of your department’s lessons learned as they develop. You can also review the lessons learned during BUCP kickoff efforts or as challenges arise during approval and data fulfillment. Other departments can benefit from your experience as well to apply or tweak them for their purposes. Please share them with other departments through CalHHS data-focused subcommittees and workgroups.

We recommend conducting a discovery session with your data-sharing team and relevant stakeholders to identify the BUCP-related metrics for tracking and reporting. Some examples of data points you may want to include in your BUCP tracking process are provided in the table below:

Once you have your metrics and data points identified, create a mechanism to collect them in your data-sharing tracking system.

You should check with your department’s technology and enterprise architecture teams to identify platforms for your BUCP tracking system. Also, consult with your department’s information security team to identify any required security controls for your BUCP repository. Your selected platform for BUCP tracking should include the following capabilities:

Document repository to store BUCP’s and related documents.

Capabilities to identify and retrieve BUCPs and other documents.

Mechanism to track BUCP status and metrics.

Task tracking to coordinate BUCP fulfillment activities.

Make sure your BUCP document repository is secured with access control to safeguard sensitive information including the contents of the Specialized Security and Specialized Privacy BUCP field content.

The State of California’s Office 365 (O365) provides tools to create a BUCP tracking mechanism using Excel and Microsoft Teams.

Technology standards for metadata differ between Application Program Interfaces (API's) and data stored in databases or files. The techniques provided in the Guide to identify and describe data elements are pertinent to describing your APIs. If your data-sharing improvement effort is API- focused, reference this section during the execution of Play 5: Establish Your Metadata Repository to establish a repository compatible with API metadata standards.

Industry standards and best practices will evolve with the field. Currently, there are two widely adopted API description standards:

(OAS) is a broadly recognized metadata specification for API descriptions.

(RAML) is an API modeling language for developing and publishing API descriptions.

Which one should you use? Each option has its considerations.

If your application development team has already adopted an API description standard, leverage their work and adopt the same standard. If your API descriptions are not current, execute Plays 2 through 6 to make them current.

If an API specification standard is not already in place, you need to work with your application development and enterprise architecture teams to jointly select a standard.

A primary consideration is which standards are supported by your API Gateway/Management platform. Review your platform’s documentation to identify supported standards. Converters are available to change formats between OAS and RAML; however, this adds an additional step to your deployment process.

Another critical factor is each standard's approach to capturing custom metadata that is beneficial for data sharing, such as security classifications and statute citations. OAS 3.x provides embedded in the description file. RAML extends its base metadata elements with Your development team should evaluate each option to determine which platform’s approach to custom metadata best aligns with their processes.

For your API descriptors to be useful, they must be easily accessible by API consumers. Check if your API Gateway/Management platform provides an API catalog to publish your APIs. If this feature is available, it is the best option as it easily integrates publishing your API descriptors into your development and deployment processes.

If your platform does not provide an API catalog, you can make your API descriptors accessible using a web server or an object store (e.g., AWS S3, Azure Blob Storage). OAS and RAML publish descriptors as JSON files that are viewable using a web browser. Your team will need to create and maintain an index webpage that contains links to your API descriptions. Be sure to include steps to publish the API descriptor and update the index webpage in your development processes.

Many data catalog platforms maintain the JSON-based formats used by both OAS and RAML, creating an option for publishing your APIs for data consumers. Using a data catalog also allows custom metadata to be captured if using extensions/overlays is not an option. Using a data catalog also provides the benefit of establishing data lineage from APIs to backend databases.

The approach described in Play 6.3: Keep Your Metadata Repository Current that integrates metadata maintenance into your development process applies to maintaining your API descriptions. RAML combines the creation of API descriptions with modeling and development. OAS generates descriptions from the underlying application code used to develop the API. Both options create a closed loop between development and descriptors to keep your API catalog current.

Your department and its staff invested in data-sharing improvements by completing the previous Plays. It’s time to put your data into use internally within your department and externally with other organizations.

This Play provides ideas about how to communicate the available data for sharing so that your department yields benefits from data-sharing improvements. Promoting data awareness and consumption is important to justify future data-sharing investments and creates a sense of accomplishment for the team that helped the Plays.

As previously noted, data-sharing improvements aren’t just for the benefit of data-requesting organizations. Your internal department teams benefit from the metadata you collected in . The Guidebook’s supplemental section, Benefits to Your Department from Executing the Plays, describes the benefits of executing the Plays. You can use this supplemental section to identify teams within your department and notify them of the enriched metadata and artifacts created in Play 6. Examples of stakeholders who may benefit from your team’s work include:

Data Analytics

Application and Data Management

Information Security

Departmental Programs

The first step is identifying internal stakeholders and teams benefitting from your data-sharing improvements. The supplement helps you identify internal analytics, technical, and security teams that benefit from your enhanced metadata repository. The notes on the department’s datasets collected in may identify programs that frequently share data within your department.

Start your data awareness campaign by emailing relevant stakeholders to notify them of the improved datasets and their benefits. Be sure to use terms that are relatable to your target audience. For example, using the term “data descriptions” is more easily understood than “metadata.” You can also schedule a Lunch and Learn or online meeting to review the benefits and how to use your metadata repository. This creates an opportunity for rich discussion about the data, how it is used, and ideas for future improvements.

Track the benefits and their impacts as your improved dataset is consumed by internal stakeholders. You can supplement your BUCP tracking repository with internal benefits to help justify investment in future data-sharing efforts.

Be sure to notify interested internal stakeholders as you incrementally improve data-sharing for new datasets.

This Play provides ideas for promoting awareness of the enhanced dataset with other CalHHS departments. A great way to promote data awareness is through the CalHHS Data Subcommittee and Data Coordinators workgroup. Participants in these groups can help spread the word about data to interested stakeholders within their departments.

The CalHHS Open Data Portal’s s a tool to identify datasets. To contribute to the open data catalog and promote awareness of your datasets, create a de-identified dataset for publication in the .

If you have datasets that other departments and organizations frequently request, publishing data-sharing information on your website is beneficial. The Department of Health Care Access and Information (HCAI) website is an example of a site that helps promote data awareness and data requestors’ understanding of data-sharing requirements.

Budget reporting may include both actuals and projected amounts. Projected amounts, although developed with models that are based on the historical actuals, reflect activities that have not yet occurred and, therefore, do not require an assessment for de-identification. Actual amounts do need to be assessed for de-identification. When the budgets reflect caseloads, but do not include personal characteristics of the individuals in the caseloads, then the budgets are reflecting data in the Providers and Health and Service Utilization Data circles of the Figure 2 Venn Diagram and do not need further assessment. However, if the actual amounts report caseloads based on personal characteristics, such as age, sex, race or ethnicity, then the budget reporting needs to be assessed for de-identification.

Many CalHHS programs oversee, license, accredit or certify various businesses, providers, facilities and service locations. As such, the programs report on various metrics, including characteristics of the entity and the services provided by the entity.

Characteristics of the entity are typically public information, such as location, type of service provided, type of license and the license status.

Services provided by the entity will typically need to be assessed to see if the reporting includes personal characteristics about the individuals receiving the services. Several examples are shown below.

Reporting number of cases of mental illness treated by each facility – if the facility is a general acute care facility then the reporting of the number of cases does not tell you about the individuals receiving the services.

Reporting number of cases of mental illness treated by each facility – if the facility is a children’s hospital then the reporting of the number of cases does tell you about the individuals receiving the services.

In (a) and (c) above, assessment for de-identification is not necessary as there are no characteristics about the individuals receiving the services. However, in (b) and (d) above, the inclusion of personal characteristics which may be quasi-identifiers, especially when combined with the geographical information about the provider, does require an assessment for de-identification.

CalHHS programs are required to provide public reporting based on federal and California statute and regulations, court orders, and stipulated judgments, as well as by various funders. Although reporting may be mandated, unless the law expressly requires reporting of personal characteristics, publicly reported data must still be de-identified to protect against the release of identifying or personal information which may violate federal or state law.

Driving towards continuous process improvement.

This is an important step as it will help us validate outcomes and determine successes. It also will help identify lessons learned, which will grow our toolbox and provide us with better intelligence. This ultimately will allow us to generate new content and additional best practices to help other Departments across the Agency.

Assess the processes involved in organizing and/or implementing the project. The focus here is on evaluating organizational and project capabilities rather than results.

Assess short term objectives, which suggest that your larger goals are being achieved. Impact evaluations are much easier to measure because they consider benefits in terms of changes in beliefs and attitudes, skills, behavior and/or policies, structures and systems.

Assess how effective you have been in meeting big picture goals. The difficulties associated with outcome evaluations include: attributing change to any one particular project; long periods between the project and being able to see change; and finding reliable and valid ways of gathering this type of information.

Establishing an evaluation process will ensure that the benefits anticipated by the implementation of any particular program or policy change are realized and an assessment can be made of the project’s overall success.

What are the lessons learned? How will you iterate on the current solution? What are the next steps?

Action Item: Continuously measure success; think critically about what your success metrics should be.

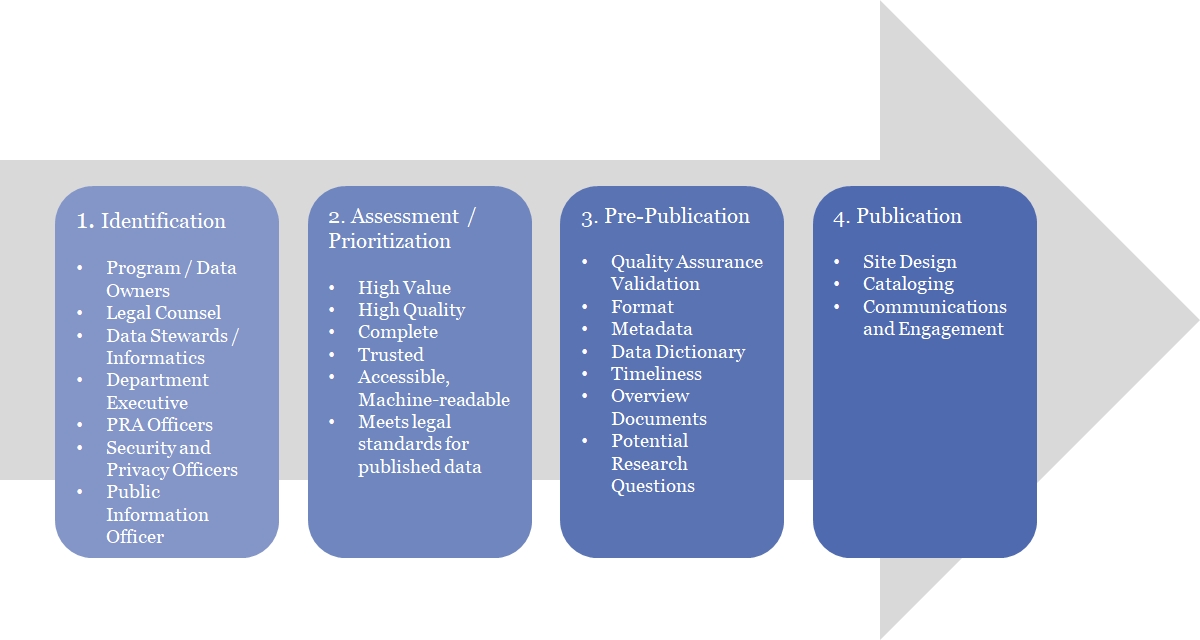

The California Health and Human Services (CalHHS) Open Data Handbook provides guidelines to identify, review, prioritize and prepare publishable CalHHS data for access by the public via the and – with a foundational emphasis on value, quality, data and metadata standards, and governance. This handbook is meant to serve as an internal resource and is also freely offered to any party that may be interested in improving the general public’s online access to data and to provide an understanding of the processes by which CalHHS makes its publishable data tables available. The handbook focuses on general guidelines and thoughtful processes but also provides linked tools/resources that operationalize those processes. The CalHHS Open Data Handbook is based on and builds upon the New York State Open Data Handbook, and we would like to acknowledge and thank the New York staff who created that document and made it available for public use.

The breadth of data and participation by departments and offices within CalHHS are continually being enhanced and expanded, making open data a dynamic, living initiative. This handbook, providing guidelines for broad publication of publishable state data in electronic, machine-readable form, is the first step in a major shift in the way CalHHS departments and offices share information publicly to promote efficiency, accessibility and transparency; and a significant improvement in the way CalHHS government engages citizens and fosters innovation and discovery in the scientific and business communities. It begins the process of standardizing the state’s data, which will make it easier to discover and use the data. Working in collaboration with others, this Handbook will be supplemented, as needed, with technical and working documents addressing specific formatting, data preparation, data refresh and data submission requirements. CalHHS and its departments and offices will use this handbook in their work as they consider various perspectives involved in governing business processes, data, and technology assets.

HIPAA covered entities in CHHS must de-identify data in compliance with the HIPAA standard. Under the HIPAA standard, either Safe Harbor or Expert Determination must be used. If Expert Determination is used then the documentation of the review is essential. The following may serve as a template for this documentation with the reference to the CHHS DDG to support the analysis documented.

Reason for Data Release:

Identify why the data release does not meet Safe Harbor. For example:

The request does not meet the Safe Harbor standard because it includes counts by county (geographic area smaller than the state) or counts by month (which does not meet the criteria for dates). Therefore, the steps in the CHHS DDG are being used to assess the tables.

After completion of the statistical de-identification process, each department will specify the additional review steps necessary for public release. This may vary depending on the purpose of the release and whether or not the department/program is a HIPAA covered entity.

Recognizing that some data analyses may be published as independent tables while other analyses will be part of larger reports, the final review of all data analyses must follow the department or office procedures for document review in addition to review procedures identified for the implementation of the DDG. The expectation is that the review of data for de-identification will fit into other routine review processes. Reviews outside the DDG portion may vary depending on whether data is being released for a PRA request, to the media, to the legislature, by the program as part of routine reporting, or for other reasons.

Departments and offices may consider the following components for reviews related to data that has been de-identified.

Statistical Review to Assess De-identification (for HIPAA entities this may be an Expert Determination Review)

As noted in , the Publication Scoring Criteria is based on a framework that has been in use by the Illinois Department of Public Health, Illinois Center for Health Statistics. Various other methods have been used to assess risk and the presence of sensitive or small cells. Public health has a long history of public provision of data and many methods have been used. Some of those methods are highlighted here.

Ohio Department of Health published a Data Methodology Standards for Public Health Practice. This method is framed around the concept that a Disclosure Limitation Standard for tabulations of confidential Ohio Department of Health data shall be suppressed when the table denominator value minus the table numerator value is less than 10.

The DDG describes a procedure, the Data Assessment for Public Release Procedure shown in Figure 5, to be used by departments in the CalHHS to assess data for public release. This section, section 4, describes specific actions that may be taken for each step in the procedure with additional supporting information being described in sections 5, 6 and 7. These steps are intended to assist departments in assuring that data is de- identified for purposes of public release that meet the requirements of the California IPA to prevent the disclosure of personal information.

The Data Assessment for Public Release Procedure includes the following steps:

Review the data to determine if it includes personal characteristics, directly or indirectly, that can be tied back to an individual;

If there is concern for personal characteristics, then assess the data for small numerators or denominators;

Supplemental: Example Metadata Repository Tools

Metadata repository platforms save time in the maintenance of your data dictionary and improve access to metadata. Data catalog platforms also make it easier to manage custom metadata, including references to applicable statutes that govern data-sharing. Data catalog platforms also promote the use of your data-sharing artifacts by improving access through web access and search functions.

Standard data catalog features include:

Automated collection of metadata from compatible data sources.

Configurable and customizable metadata labels and tags to address the specific requirements.

Reporting number of psychotropic medications prescribed by a general psychiatrist to include the number of medications prescribed by the age group, sex or race/ethnicity of the patients receiving the medications does tell you about the patients receiving the medications.

Step 1 – Presence of Personal Characteristics

Summary:

Step 2 – Numerator Denominator Condition

Summary:

Step 3 – Assess Potential Risk

Summary:

Step 4 – Statistical Masking

Summary:

Step 5 – Expert Review

Summary:

“Risk is very small that the information could be used, alone or in combination with other reasonably available information, by an anticipated recipient to identify an individual who is a subject of the information”

Legal Review

Departmental Release Procedures

The department or office may designate individuals within the department to provide a statistical review of data products before they are released to ensure the data has been de-identified with methods that are consistent with these guidelines.

For HIPAA covered entities, this will be performed by individuals who are considered experts for the purpose of performing expert determinations in compliance with the HIPAA Privacy Rule, and who meet the Rule’s implementation specifications: “A person with appropriate knowledge of and experience with generally accepted statistical and scientific principles and methods for rendering information not individually identifiable” [45 CFR Section 164.514(b)(1)] This expert determination review, according to the regulation’s requirements, will be performed by:

45 CFR section 164.514 (b)(1) A person with appropriate knowledge of and experience with generally accepted statistical and scientific principles and methods for rendering information not individually identifiable:

(i) Applying such principles and methods, determines that the risk is very small that the information could be used, alone or in combination with other reasonably available information, by an anticipated recipient to identify an individual who is a subject of the information; and

(ii) Documents the methods and results of the analysis that justify such determination

When an expert determination review is requested, the Expert Determination Review must include a document that includes the expert’s determination that “the risk is very small that the information could be used, alone or in combination with other reasonably available information, by an anticipated recipient to identify an individual who is a subject of the information,” attests that the requirements of 45 CFR section 164.514 (b)(1)(i) and (ii) have been met, and includes (or attaches) the documentation required by 45 CFR section 164.514(b)(1)(ii). This document must be signed by the expert.

These guidelines provide a starting point for expert determination review; however, the facts of each case chosen for expert determination review must be analyzed on an individual, case-by-case basis by the expert. If followed, the Guidelines may be referenced as part of the documentation used to support the expert determination. The documentation should also include a general description of the principles, methods, and analyses used, as well as an explanation of the analysis that justifies the expert determination.

The expert determination review may use the Expert Determination Template in Appendix A. The Expert Determination Template includes a confirmation that “the risk is very small that the information could be used, alone or in combination with other reasonably available information, by an anticipated recipient to identify an individual who is a subject of the information.”

If methods that have been used to de-identify the data are not described in the Guidelines, then the Expert will need to provide additional documentation that explains the statistical and scientific principles and methods used and the results of the additional analysis.

Step 5 in the Data Assessment for Public Release Process provides for a legal review within the department. This may vary depending on the purpose of the release and whether or not the department or program is a HIPAA covered entity or not. This review may assess the data to be released for risk to the Department, and for potential implications on litigation, statutory or regulatory conditions on data release, and other legal considerations that may impact release. Legal Services may review the expert determination documentation to ensure compliance with the HIPAA Privacy Rule as applicable.

Step 6 in the Data Assessment for Public Release Process provides for departmental release procedures for de-identified data. After completion of the statistical de- identification process, each department will specify the additional review steps necessary for public release of various data products. Products may include but are not limited to reports, presentation, tables, PRA responses, media responses and legislative responses.

Potential reviews include Public Affairs. Public Affairs is often designated to receive all publications, brochures, or pamphlets intended for public distribution to be printed or reproduced to review the material to determine if it requires Agency Approval or Governor’s Office approval. Public Affairs may also be designated to review content to assess the data table for compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA).

Departments may also consider processes for quality assurance reviews: The may apply to data products being added to the web sites to ensure that they have had appropriate reviews and de-identification steps. It may also include reviews of updated reports. Many reports maintain the same variables and formats but have updated numbers/information on a periodic basis (monthly, quarterly, annually). For these reports, departments may consider a centralized review to ensure data products are consistent with previously reviewed reports and have not had changes that would change the previous assessment.

Broad support for metadata types, including databases, APIs, and Commercial Off the Shelf (COTS) products.

Compatibility with both cloud and on-premises database platforms.

Store metadata across data sources (e.g., Databases, APIs)

Commercial and open-source platforms are available. Sparx EA (Enterprise Architect) is a commonly used tool that provides data dictionary functionality that may already be in use by your department's Enterprise Architecture team. Your metadata must be widely accessible to be useful. Your selected tool must be easy to use for non-technical staff.

Some example open-source offerings include:

If you elect to use an open-source platform, please have the product evaluated for your department's security and open-source use/license policies.

If you prefer a commercially supported product, there are many available options. Some open- source platforms offer Software as a Service (SaaS) options to access product support and avoid infrastructure maintenance.

A big advantage of general use data catalog products is the ability to store metadata beyond

just your data department’s databases. Many platforms support data cataloging for data sources including:

APIs

Data Extracts

Data Created in Reports

These platforms typically provide useful functions including the ability to Entity Relationship Diagrams (ERD) diagrams and data lineage (traceability) across datasets.

Metadata repository Software as a Service (SaaS) offerings are available from the California Department of Technology (CDT) Off-Premises Cloud Services providers. These products have a low cost and are easily procured. You will need to verify that the cloud-based data catalog products are compatible with all data platforms that are the source of your metadata. Due to their low cost, adopting a cloud-based data catalog platform may be worth considering if it is compatible with your priority data sources. Most of these platforms allow spreadsheet uploads to address other data sources.

If a trial or SaaS option is available, it is a good practice to conduct a proof of concept (POC) before you make a final selection. Additionally, we recommend conducting a pilot with a single dataset before widespread adoption to verify your metadata schema and develop training materials.

3/3/2025

R. Swift

Updated document for web formatting, updated abbreviations/acronyms, and links where appropriate.

1.1

10/1/2016

CHHS

Added [references and links to] CalHHS De-Identification Guidelines

1.0

1/1/2015

CHHS

Initial release

These four terms are highlighted because they are frequently used throughout this document. Additional terms and definitions are listed in the Glossary.

A value or set of values representing a specific concept or concepts. Data includes but is not limited to lists, tables, graphs, charts, and images. Data may be structured or unstructured and can be digitally transmitted or processed.

An organized collection of related data records maintained on a storage device, with the collection containing data organized or formatted in a specific or prescribed way, often in tabular form. In this handbook the dataset refers to the master, primary, or original authoritative collection of the data.

A data table, in this handbook, refers to a subset of the dataset which may include a selection and/or aggregation of data from the original dataset.

Data is Publishable State Data if it meets one of the following criteria: (1) data that are public by law such as via the Public Records Act or (2) the data are not prohibited from being released by any laws, regulations, policies, rules, rights, court order, or any other restriction. Data shall not be released if it is highly restricted due to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (“HIPAA”), state or federal law (such data are defined as Level 3 later in this handbook).

Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment published Guidelines for Working with Small Numbers which also addresses many of the same topics.

The size of numerators and denominators vary in each of the documents above although the principles are consistent.

Access control to limit access to sensitive information (Specialized Security) to specific staff.

BUCP Fulfillment Duration

Identify the impact of data-sharing and process improvements.

Quantitatively demonstrate the impact of data- sharing investments.

Provide metrics for staff planning.

Identify BUCP process points that impede progress.

BUCP Outcome (Approval, Denial)

Identify needed investments to improve BUCP approval probability.

Provide a source of “lessons learned” to optimize the data-sharing process.

Disputes and Resolutions

Use to create metrics on the frequency of disputes and resolutions.

Statutory Restriction Solutions

Provide a repository to identify approaches (e.g., Data Aggregation, De-Identification) to resolve data-sharing restrictions.

Data-Sharing Outcome and Results

Track the outcome and results of data-sharing to secure management support for investment in related capabilities and staff.

1.0

6/1/2016

CalHHS

Initial Release

1.0

3/3/2025

CalHHS

Initial release of combined product

1.0

12/1/2025

CalHHS/OTSI

Initial Release

2.0

7/1/2017

CalHHS

Added CalHHS sharing materials, other resources

1.1

10/1/2016

CalHHS

Added [references and links to] CalHHS De-Identification Guidelines

1.0

6/1/2016

CalHHS

4.1

8/1/2021

CalHHS

2.0

7/1/2017

CalHHS

Added CalHHS sharing materials, other resources

1.1

10/1/2016

CalHHS

Initial Release

Added [references and links to] CalHHS De-Identification Guidelines

If there is concern for small numerators or denominators, assess potential risk of data release;

If there is potential risk identified, assess the need to apply statistical masking methods to de-identify the data;

Following statistical de-identification, the data release is reviewed by legal if indicated in departmental procedures; and,

After statistical de-identification, the data is reviewed and approved for release based on program and policy criteria pursuant to departmental procedures.

The steps above are represented in a step-wise process shown in Figure 5. Each step is described in further detail in section 4.1 through 4.6.

Data summaries that originate from data which includes personal identifiers must be de- identified before release to the public. Additionally, data summaries about conditions experienced by individuals must be adequately de-identified to prevent re-identification of individuals represented by the summarized data. Various statistical methods are available to statistically de-identify data.

Summarized data may be reviewed in the context of the numerator and the denominator for the given presentation. The numerator represents the number of events being reported while the denominator represents the population from which the numerator is taken. For example, if it is reported that there are 50 cases of diabetes in California then the numerator would be the number of cases (50) and the denominator would be the number of people in California that could have diabetes (more than 38 million people since diabetes can occur at any age or sex). While the numerator is relatively straight-forward to identify, the denominator can be difficult. Data summaries are frequently presented in tables in which numerators and denominators may be identified.

The numerator is typically the value in each table cell. However, the denominator can be difficult to identify given the various ways in which tables are prepared. Two examples of tables, Figure 3 and Figure 4, show the numerators and denominators in sample tables.

Figure 3 shows an example table with the numerator and the denominator highlighted. The Cells in the table are the boxes with values in them, as opposed to the row and column headings. The row headings are 2012 and 2011. The column headings are Year, # of Medi-Cal Members in Fee For Service (in thousands) and Number of Medi- Cal Members in Managed Care (in thousands). In Figure 3, “2,775” is the value in a table cell and represents a numerator. The sum of the row for year 2012 (2,775 + 4,853

= 7,628) represents a denominator. In this context, the denominator may represent row totals, column totals or the total occurrences in the data set released. Data in Figure 3 comes from the “Trend in Medi-Cal Program Enrollment by Managed Care Status - for Fiscal Year 2004-2012, 2004-07 - 2012-07.”

Figure 4 shows another type of table that contains rates. In this case, the numerator is the number of Salmonella cases for a sample of California Local Health Jurisdictions in 2014. The table also includes the rate of Salmonella for these jurisdictions. In order to calculate the rate, the population size of each jurisdiction is required, but is not shown directly in this table. The population denominator is an important element for data de- identification.

Discovery sessions are an effective approach to effectively gather information from staff across your department. There is no set format for a discovery session. Discovery session questions will be context-specific to your department’s needs and the program(s) related to a data set.

Some key aspects of an effective discovery session include:

Research Ahead of Time: Review any available data architecture and program documentation to identify initial questions and build context before the discovery session. Reviewing materials ahead of the meeting also ensures efficient use of participant time.

Prepare Your Questions: Creating a set of discovery questions helps ensure you obtain the information you need on the data set. Be prepared for additional topics and questions to arise organically during the discovery session.

Capture the Information: Ideally, have one person ask the discovery questions while another captures meeting notes. Often this is impossible. If acceptable to the participants, record the meeting for later review.

Confirm Your Understanding: Communicate your understanding to participants for confirmation and clarity.

When scheduling discovery sessions, include context for the effort and the objectives for the discovery session. To establish a common understanding, the session should start with a definition of data-sharing; examples of data-sharing help provide additional context. The provides some short videos that review impactful data-sharing efforts.

The article from UX Everything provides useful tips for preparing and conducting discovery sessions.

Statistical masking provides an extensive set of tools that can be used to mitigate potential risk in a given data presentation. As discussed in Section 4.4, the data releaser will assess the need for statistical masking when the assessment in Step 3 identified potential risk. Each department will document statistical masking processes that are routinely used in data preparation for public release.

As discussed in section 4.4, initial methods to address sensitive or small cells, as well as complimentary cells include the following:

Reduce Table Dimensions

Reduce Granularity of Variable(s), aka Recoding or Aggregation

The DDG workgroup reviewed the published literature including information from other states and from the federal government. There was a great deal of variation in the numerical values chosen for the Numerator Condition. While the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) WONDER database suppresses cells with numerators less than 10, the National Environmental Public Health Tracking Network suppresses cells that are greater than 0 but less than 6. Examples range from 3 to 40 with many being 10 to 15. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) uses a small cell policy of suppressing values derived from fewer than 11 individuals. As stated in a 2014 publication associated with a data release of Medicare Provider Data, “to protect the privacy of Medicare beneficiaries, any aggregated records which are derived from 10 or fewer beneficiaries are excluded from the Physician and Other Supplier PUF [public use file]

A critical step in reviewing data for public release is the consideration of what other data may be publicly available that could be used in combination with the newly released data to identify the individuals represented in the data. This section will highlight some specific data sets that are publicly available that may be used in combination with CHHS data that would contribute to potential increased risk.

Common kinds of data with personal information include: real estate records, individual licensing databases (MD, RN, contractors, lawyers, etc.), marriage records, news (and other) media reports, commercially available databases (data brokers, marketing), court documents, etc.

Another common data set for programs to be aware of are the publicly available electronic birth and death indices from Vital Records, as specified in Health and Safety Code section 102230(b).

CalHHS programs develop a wide range of information based on different types of data. This is reflected in the various categories shown on the entry page for the CalHHS Open Data Portal, which include:

Diseases and Conditions

Facilities and Services

Healthcare

The CHHS Data Subcommittee requested the convening of the CHHS Data De- Identification Workgroup to develop the DDG.

The DDG Workgroup began with an orientation to the topic of data de-identification and presentations by the DHCS, OSHPD and California Department of Public Health (CDPH) regarding current practices and activities related to data de-identification. The DDG Workgroup used the Public Aggregate Reporting for DHCS Business Reports (PAR-DBR) as a starting point for initial drafts. The PAR-DBR had been developed between April and August, 2014 through a workgroup processes within DHCS with input and presentations from OSHPD, CDPH, and University of California, Los Angeles California Health Interview Survey. The PAR-DBR served as a basis for this document, including the literature review conducted as part of the development of the PAR-DBR.

The development process was designed to include an updated literature review, case examples and broad discussion among CHHS programs. Publishing data publicly is always a balance between the protection of confidentiality and the usability of the data.

The project timeline for the CHHS DDG Workgroup is below:

CalHHS collects, manages, and disseminates a wide range of data. As departments classify data tables and catalog their publishable state data, they should be mindful of legal and policy restrictions on publication of certain kinds of data. Following are general guidelines regarding disclosure to consider as departments begin to identify and review data tables.

The CalHHS Data Subcommittee commissioned the development of Agency-wide guidelines to assist departments in assessing data for public release. The are focused on de-identification of aggregate or summary data. Aggregate data means collective data that relates to a group or category of services or individuals. The aggregate data may be shown in table form as counts, percentages, rates, averages, or other statistical groupings. Refer to the for the specific procedures to be used by departments and offices.

This section will help Departments move from conversation to action. It will provide resources that will allow the Departments to succeed. This might include: roles and responsibilities; governance structures; and data standards. It also includes resources on project management and change management to help both staff implement and leadership enforce the importance of this work.

This content moves away from the theoretical and drives toward the tactical.

By detailing all critical steps before starting the project, the Department can anticipate factors they otherwise would not consider until encountered and identify potential problems and challenges on the front end.

The planning becomes proactive instead of reactive, which allows best practices to be used and ensures that energy and time are spent on implementing a high-quality, well‐thought‐out project rather than "putting out fires."

The planning and implementation processes will allow any person working on the project, regardless of his or her level of involvement, to fully understand the goal of the project and how it is to be accomplished. It ensures that everyone working on the project is on the same page and that any discrepancies are resolved before they become costly to the project or population served.

This play includes various resources designed to help with project management and data management.

Small cell sizes are typically encountered when one of the following conditions is met.

Multiple variables. This most often occurs in a pivot table presentation or a query interface where a user may have occurrences of disease X, stratified by county, stratified by sex, stratified by race and ethnicity.

Granular variables. The more granular the variable the smaller the potential numerator and denominator. This most commonly occurs with shortening the time period of reporting (weekly) or making the geography more specific (zip code or census tract). However, it can also occur when there are many categories for a variable. An example of this is aid codes in Medi-Cal where there are almost 200 aid codes.

Rare events. Examples include diseases such as hemophilia. Examples of incidents may result from mass trauma events such as a plane crash or multi- car accident.

In each of these cases, statistical masking may be addressed in a number of ways. For this reason, it is important to keep in mind the purpose for the reporting so that the method chosen for masking can still maximize the usefulness of the data provided. Choices for each condition are highlighted below.

Multiple variables. Options include separating the table into multiple tables that limit the number of variables included in each table; decreasing the granularity of the variables included in the table; or suppressing the small cell with an indicator that it is less than 11.

Granular variables. A common approach to this situation would be to decrease the granularity of the variables although suppressing the small cell with an indicator that it is less than 11 is also an option.

Rare events. In these cases it becomes very challenging to suppress the value in a way that it will not be able to be used with other public information to identify individuals. Additionally, with rare events, there is more significance in the variance of small numbers.

In addition to small cells, complementary cells must also be suppressed. Complementary cells are those which must be suppressed to prevent someone from being able to calculate the suppressed cell based on row or column totals in combination with other data in that row or column.

Suppressing small cell values and complimentary cells can be done in two ways.

Use a symbol to indicate the cell has been suppressed. Identify any other cells (complimentary cells) that can be used to calculate the small cell and use a symbol to indicate the cell has been suppressed.

Use a symbol to indicate the cell has been suppressed or leave the cell blank and remove the value from all pertinent row and column totals so that the cell cannot be calculated. This negates the need for evaluation of complementary cells. This method must be used with great caution because the totals may actually be published in other non-related tables. For this reason the method is not recommended.

When suppressing values, the following footnote to indicate the suppression is recommended:

“Values are not shown to protect confidentiality of the individuals summarized in the data.”

In addition to the above, there are a number of other methods that may be used for Statistical Masking. Methods discussed in the “Statistical Policy Working Paper 22 (Second version, 2005), Report on Statistical Disclosure Limitation Methodology” include the following for tables of counts or frequencies and for magnitude data.

Tables of Counts or Frequencies

Sampling as a Statistical Disclosure Limitation Method

Defining Sensitive Cells

Special Rules

The Threshold Rule

Protecting Sensitive Cells After Tabulation

Suppression

Random Rounding

Controlled Rounding

Controlled Tabular Adjustment

Protecting Sensitive Cells Before Tabulation

Tables of Magnitude Data

Defining Sensitive Cells – Linear Sensitivity Rules

Protecting Sensitive Cells After Tabulation

Protecting Sensitive Cells Before Tabulation

Just as there is no consistent value for the Numerator Condition, neither is there a consistent value for the Denominator Condition. Some examples include:

National Center for Health Statistics (public micro-data) – 250,000

National Environmental Health Tracking Network – 100,000

Maine Integrated Youth Health Survey – 5,000